Between Land and Sea: Mangroves

By Jia

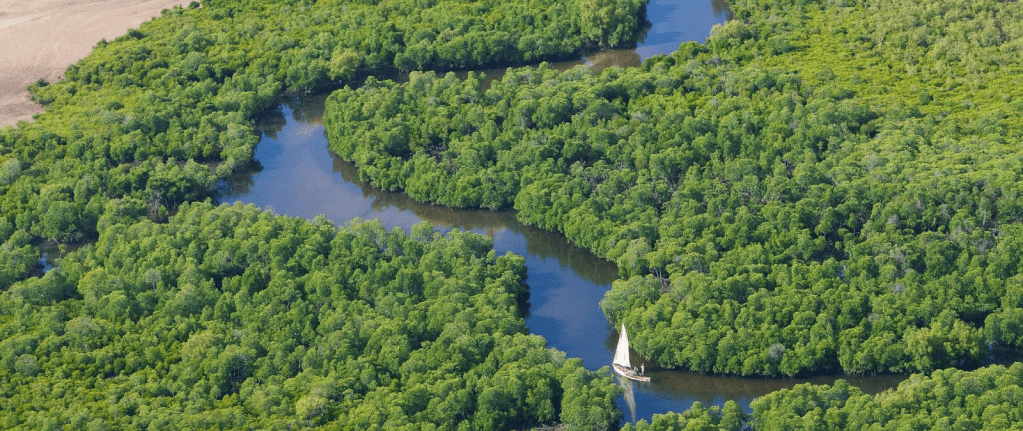

Over the past 40 years, the world has lost more than 20% of its mangroves, a quiet piece of the climate crisis unfolding. Along the edges of warm tropical coastlines, anchored in mudflats or the mouths of rivers grows one of the planet’s most extraordinary ecosystems: the mangrove forest. These trees thrive where few other plants survive, in salty and poor oxygenated environments, protecting this planet and countless species. Their destruction may seem distant especially as they grow in very few regions but their impact means much more.

Why Mangroves Matter

Mangroves protect both people and nature, which sometimes goes unnoticed. Their intricate root systems act as natural infrastructure protecting coastal communities from storms, floods and erosion. Beneath the surface, mangrove roots also provide nursery grounds for numerous species of fish and other marine life. In fact, more than 1500 species from birds to reptiles depend on mangrove ecosystems. In reality, these coastal communities depend on the ecosystems that mangroves provide for these animals, as many people’s livelihoods come from fisheries, which would not be possible without them.

Their value does not end there, as mangroves clean the water by trapping pollutants and sediments. However, mangroves biggest impact is that they are among the most effective carbon sinks on Earth, storing carbon not only in their trunks and branches but deep in the soils beneath them. Though they make up less than 1% of tropical forests, they can hold up to 10 times more carbon than other forest types. By locking away vast amounts of carbon, mangroves reduce the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and help slow global warming.

The Destruction of Mangrove Forests

The destruction of mangrove forests has an immense impact on the environment. When they are cleared for shrimp farms, coastal development, or logging, centuries of stored carbon are released back into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change.

Biodiversity suffers as well. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), 15% of all species linked to mangroves are now threatened with extinction. Nearly half of the mammals that rely on them are at risk. Also, the short-term profits that people might gain from destroying these forests ignore the long-term detriments like losing protection from storms, declining fish populations and poorer water quality.

Kenya: A Case Study in Conservation

Kenya’s coast tells a different story: one of renewal and innovation. About 65% of Kenya’s mangroves are found in Lamu County, where they protect the local communities. This year, the new HS Swahili Culture trip visited the Mikiko Pamoja Project. Mikiko Pamoja is a global example of community driven conservation. It is the first project in the world to sell carbon credits from restoring mangroves. The money earned funds local schools, clean water and health initiatives, which are reinvested into the communities that support the project.

Since 2022 ISK has collaborated with LEAF, a community run project in Kilifi, as part of our offsetting and sustainability initiative to help ISK meet its commitment to become carbon neutral by 2030. Our HS Coastal Conservation trip visits the community and helps plant and clean mangroves. Read the story here on the Carbon Neutral Alliance website.

These projects show that protecting mangroves is not only about saving trees. It is about involving these communities and showing how nature and people are connected.

Femicide in Kenya: Its Roots, Impacts, and Recent Resurgence

By Anonymous

On September 5th 2024, Olympic athlete Rebecca Cheptegei was set on fire and murdered by her ex-boyfriend at her home in western Kenya. Gender-based violence is not a new phenomenon and has been recorded to exist ever since ancient Rome, in which men could legally decide if their wives lived or died. Although this is an example of an extreme case of gender-based inequality and permittance of gender-based violence, femicide has certainly not been eradicated. According to Africa Uncensored, in Kenya, deaths due to femicide have increased drastically since 2024, setting a worrying precedent for the future of women in Kenya. Femicide is the murder of a woman or girl due to her gender.

In reported cases, approximately 127 women in Kenya were murdered due to femicide. Because this only includes the reported cases, it is highly likely that the actual number of deaths is higher. According to Africa Data Hub, approximately 68% of femicides in Kenya in 2024 were caused by the victim’s current or past male intimate partner, highlighting how the predominant demographic of people who commit femicides in Kenya is not only men, but men who know the victim personally. This then begs the question: Why are men (who the victims were personally familiar with) the main perpetrators of femicide? It could be argued that there is no universal motive and that the woman’s actions as an individual is what led the men to commit murder, but the disproportionate amount of men who committed murder suggests societal norms and inculcation at large contribute to (if not cultivate) violent behavior in men against women.

Furthermore, according to Laura Darcey, the belief that women should be subservient to their husband/male partner is pervasive throughout Kenyan society. The man is also expected to be dominant, strong, and capable. He is supposed to be the provider. While there is nothing inherently wrong with possessing these qualities, if the man is simultaneously taught to suppress his emotions and restricts freedom of emotional expression to displays of violence and anger alone, so-called masculine qualities can become the catalyst for extreme insecurities. As a result of crushing societal expectations and a deep-seated insecurity of feeling unable to fully achieve them, men express themselves in the only way their extrinsic motivators allow them to: violence. Additionally, the woman in this idealized dynamic is instructed to be submissive, appeasing (of the man), and subservient. Thus, the man is enabled to (if he does not already perceive it to be within his rights) express his pent-up emotions and frustrations against the woman. This often manifests in the form of physical and/or sexual violence.

Kenya also has fewer legal protections against spousal/domestic violence than other countries. According to James Mulei, Kenya does not criminalize spousal rape, meaning it can only be punished under laws covering non-sexual assaults. This, paired with police corruption and many perpetrators being able to dodge conviction or trial through the bribery of police and/or their political connections makes it so many perpetrators of spousal violence roam free without facing any consequences. The corruption and lack of legal protections helps perpetuate the insidious spread of femicide and gender-based violence. If legal consequences are not present and enforced, perpetrators would not only not see justice for their crimes, but they would have the ability to continue to assault or murder more people.

Attempts to bring an end to femicide in Kenya and advocate for the survivors have existed in the forms of protests and media campaigns, but have been largely unsuccessful. According to Monicah Mwangi, in March 2024, hundreds of people marched into the capital city Nairobi against femicide. They blew whistles and chanted “Stop killing women!” Kenyan police acted quickly and from moving vehicles, fired tear gas into the crowd of protesters. Additionally, many protesters were arrested by the police. The fact that peaceful protest was smothered so violently highlights the power imbalance between citizens and the police, and further lends credence to the notion that the Kenyan police are unreliable when it comes to protecting the country’s people and ensuring their safety.

Femicide is an insidious issue in Kenya that largely stems from patriarchal norms and toxic masculinity. In order to minimize future instances of femicide, legislative reforms,such as criminalizing spousal rape, should to be taken in order to protect women. Additionally, reforms within culture, law enforcement, and communities need to take place as well. It will be a gradual process, but is necessary for the safety of all women in Kenya.